Codes + Identity

Inner Tides and Travels in the Blood: New Works by Guy-Vincent

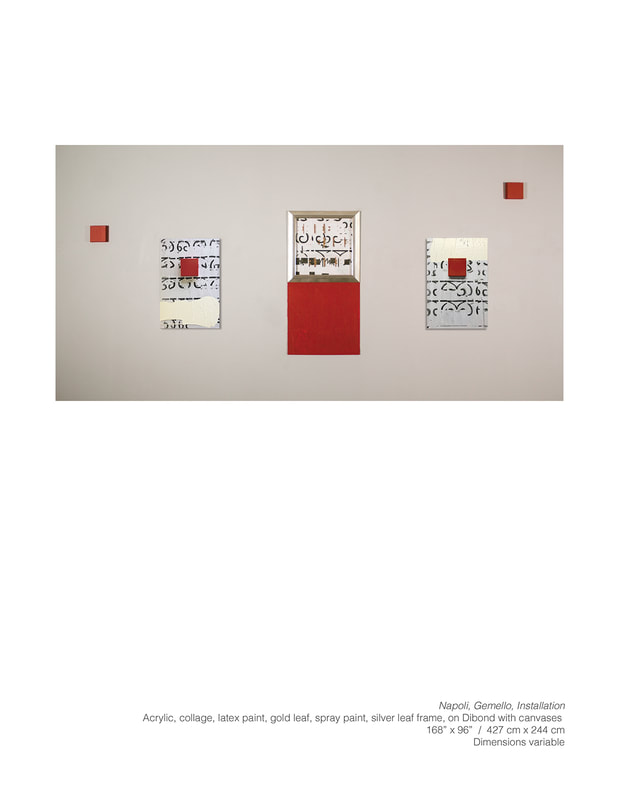

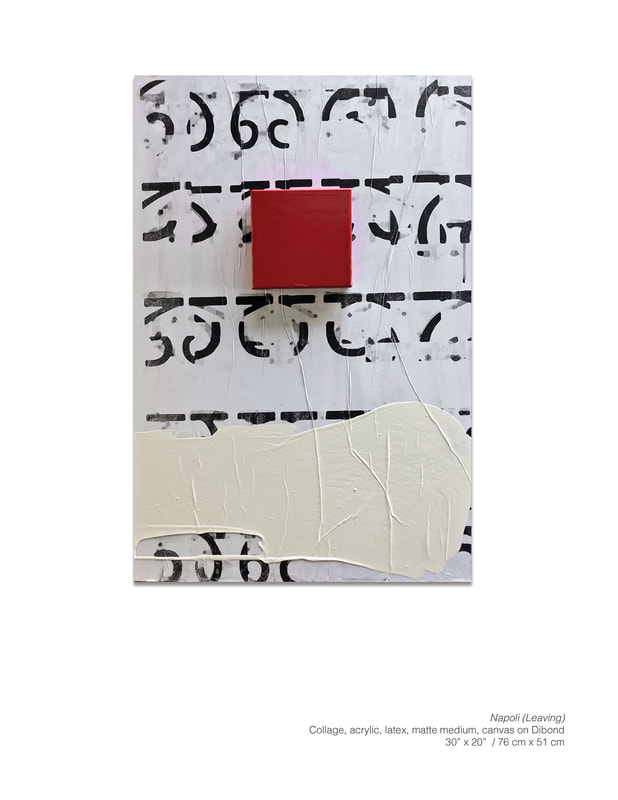

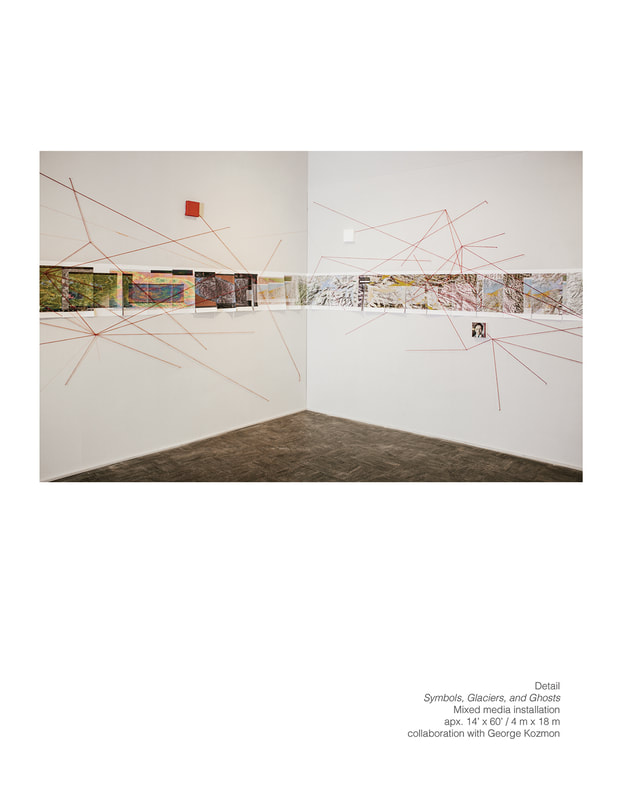

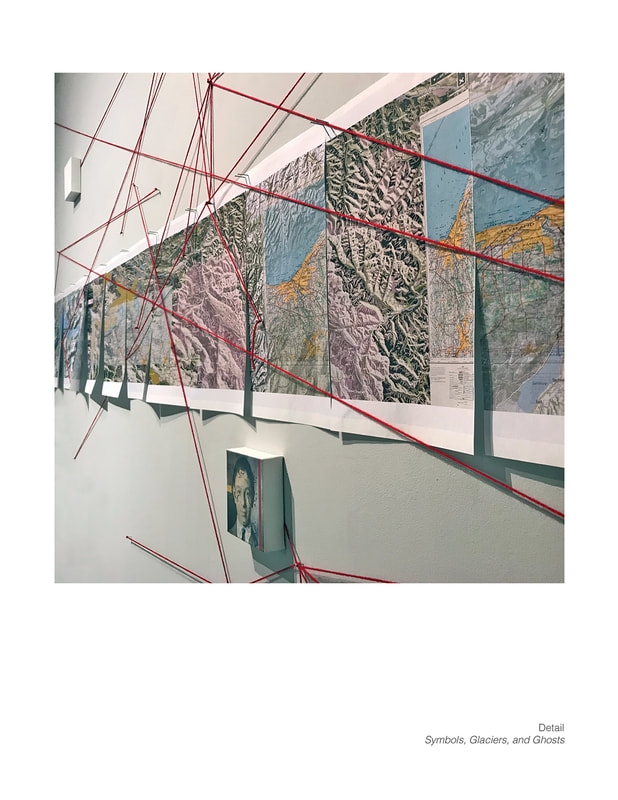

Guy-Vincent’s often scroll-like mixed media works re-imagine the long, opaque quality of time’s passage, and the persistence of human identity half-submerged in its tide. Working on canvases or Dibond panels abutted in series, or on very large sheets of thick artists’ paper, GV mixes images and calligraphic marks, half-painted over as if with white-wash, or perhaps (metaphorically) sea-foam. These written traces and forms float in pentimento-riddled layers, hinting of mythic paradigms and distant epochs. Their overlapping suggests the circulation of information and differing perspectives, rolling between contemporary communications technologies and the genetics of genealogy.

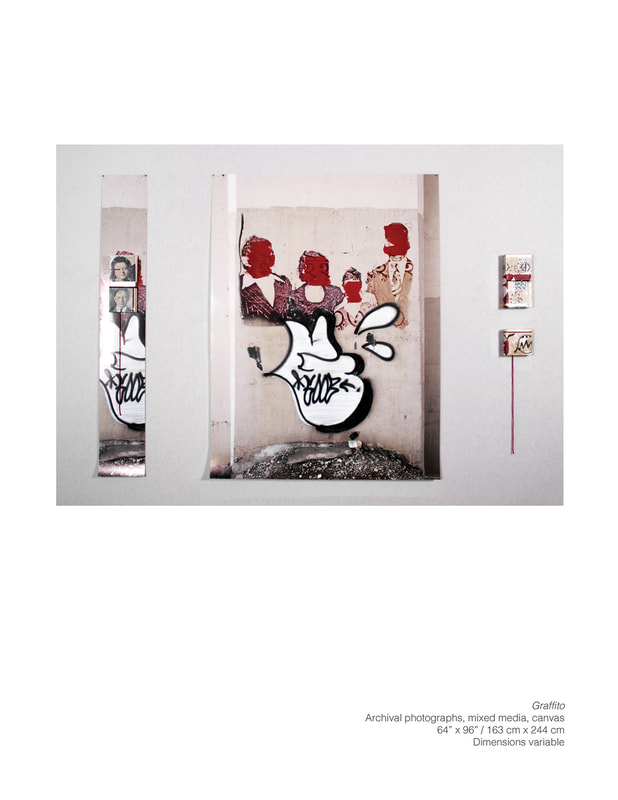

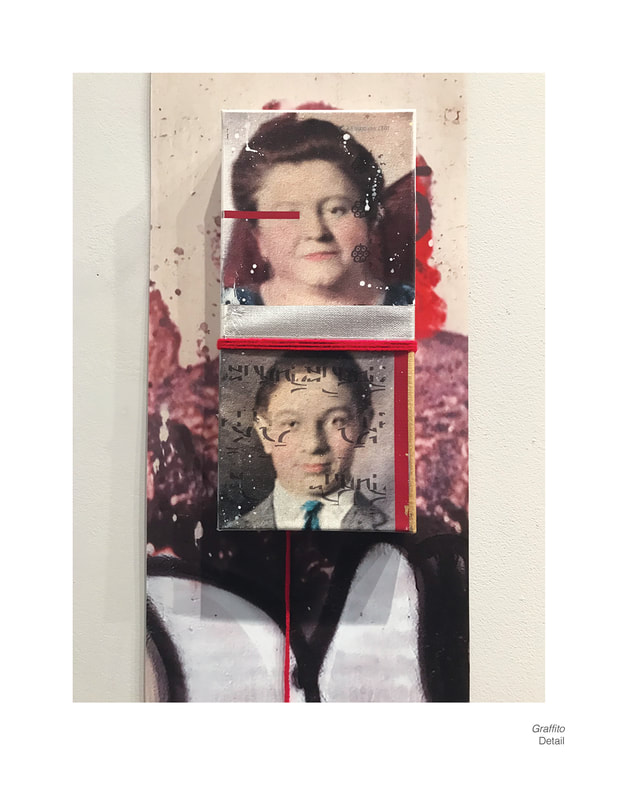

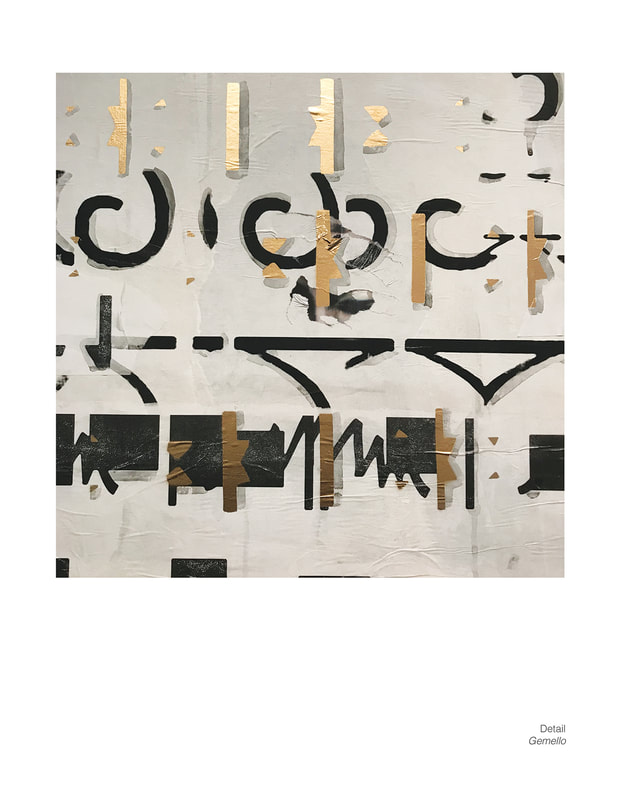

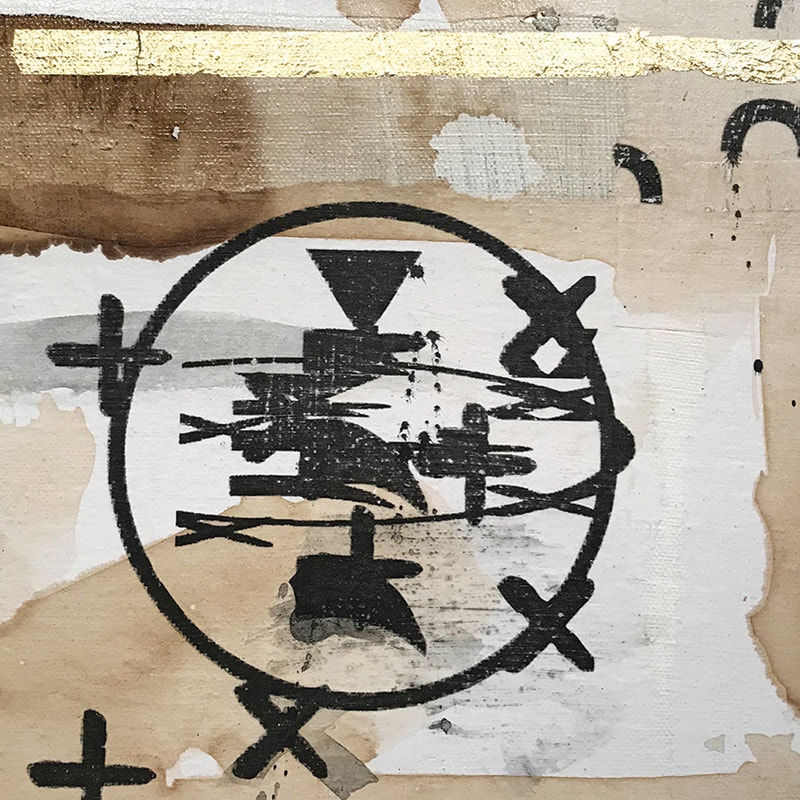

In his search for a personal artistic language GV first turned to personal documents and photographs, which traced his own family’s spread across the Atlantic to the New World. Emotionally powerful large-scale blowups of faces and buildings became emblems of vanished worlds in these works, stained and crisscrossed with areas of red and white. Traces of mysterious marks appear and disappear like half-buried ornamental friezes or inscriptions in an ancient alphabet -- like the trove of ancient, daily records recently identified on papyri used as Egyptian mummy wrappings. GV’s half-pictorial marks (which he generates from manipulated typescript) are now characterististic of his works as a whole, along with other expressive gestures, especially pools or stains of white and red paint. They reflect GV’s long-standing interest in graffiti and well-known symbolic languages, like standard text-driven computer programs and the pictorial potential of numbers and letters, serifs and punctuation. Since the 1990’s GV’s work has operated at the boundaries of public and private expression, emphasizing formal qualities of modern communications activities, linking fine art to advertising and propaganda. Always concerned with what could be called the aesthetics of data, both big and small, he now moves more quickly though human cultures, using vehicles available on the internet. GV’s more playful expressions have become widely known on Twitter and Instagram, especially his hypnotic video loops and graphic experiments, which turn patches of ASCII into micro-gardens of interlocking shapes and lines.

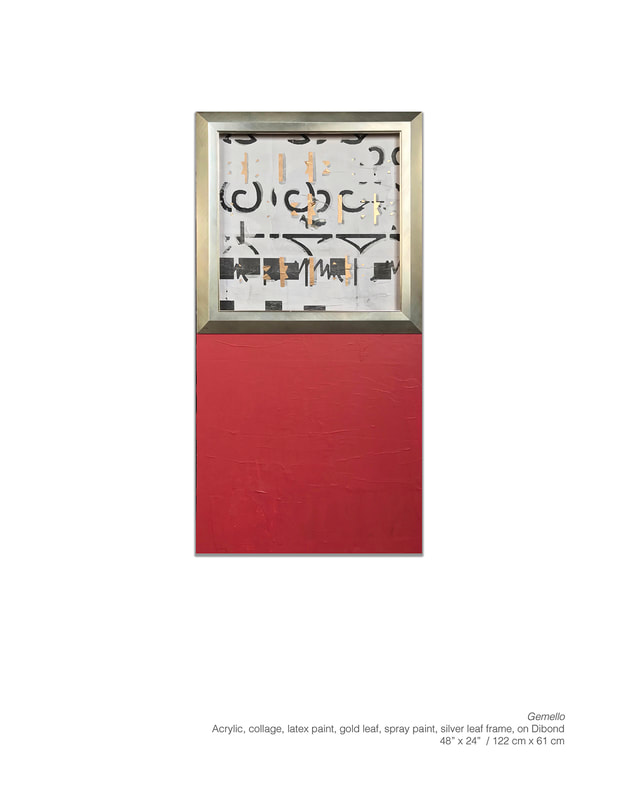

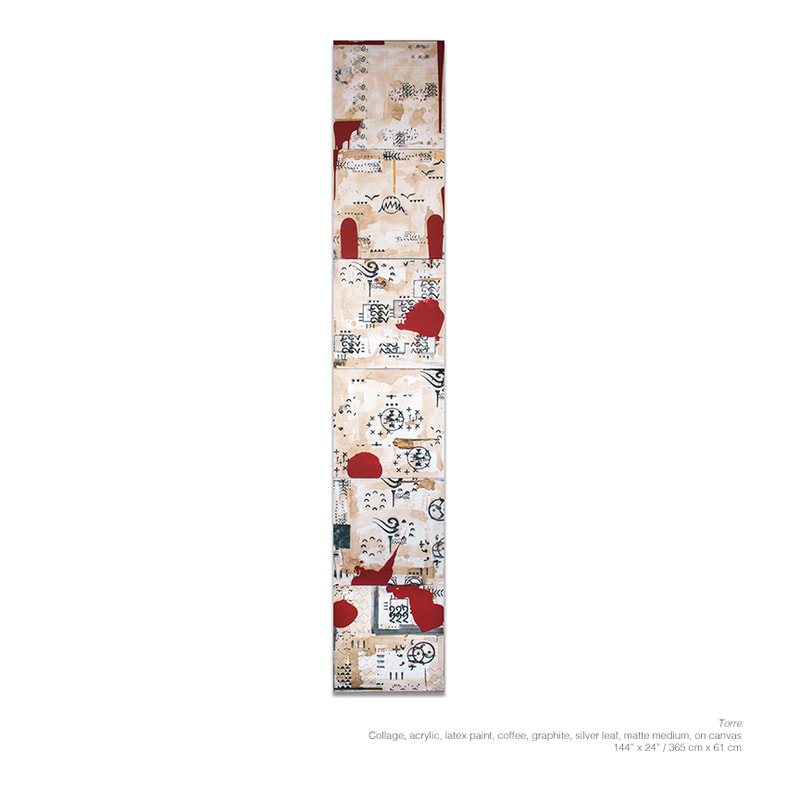

In the show “Codes and Identity” new works like “Torre” (“Tower” in Italian) are as much as fifteen feet tall, or lead for yards across the wall horizontally like watchtowers or canals. Throughout the current exhibition they look a lot like documents, but also like the spires and itineraries of great journeys. Encoded in their shapes and dimensions are memories of the scope and reach, the sheer scale of human migration, reminding us of the maps made with feet that have unfolded across the earth and oceans of every family’s past. In their details they sample a dimension of record-keeping and mark-making that has existed alongside every civilization from its rudest beginnings. Sumerian tablets, hieroglyphic inscriptions, petroglyphs and the tally marks and symbolic knots of herding cultures, Babylonian star maps and the invention of mathematics, all can be glimpsed beneath the membrane of our own cultures systems of symbols. The fact that through not only theory but microphotography we know that our own bodies and everything living are in some sense “written” by DNA, inscribed in reality by streaming, chemical sentences which actually look like a kind of writing, is a sort of graphic parallelism that also sets off its echoes throughout GV’s reveries. Gradually a sketchy semiology of the self emerges – phrases composed of paint and ink and imagery, overwritten with traces of written languages in several languages and alphabets around the globe. A large vision of humanity’s deep history and far-reaching webs of communication hang behind the columns and friezes of his symbolic improvisations, and a sense of persistent human personalities, peering from forgotten times and moments infinitely numerous.

“Tempo,” which is four feet by 185 inches, unwinds the hidden trails and traumas of a long trip, long ago. Here as elsewhere one of GV’s tropes is the idea of musical notation, as it measures song and sound, emotion and duration, stepping along the staff. So much information is packed into a few lines, somewhat as worlds of experience and ability, of differentiation infuse every micromillimeter of organic matter. In this work GV uses graphite and spray paint, gesso and latex and coffee, spread, poured, or inscribed on canvas. Near the beginning, along at the top of the first (perhaps) or left-hand section, can be seen the face of a serious, old-fashioned boy, dressed up in a tie and formal jacket, as if for a passport photo or a confirmation celebration. The photo – and the face – recur near the right-hand margin of the piece, much larger this time, as if nearer. In between there are many rectangles that could be windows, or parts of a filmstrip, or train cars. And here and there a bristling little linear ridge, like an indication of a mountain range, appears through the stained manuscript-like surface. It could be a quick sketch in a letter home, o just a doodle. The first panel ends with a column of red, accompanied by a vertical series of marks that might represent a number. At the bottom corner of a middle area a puddle of red forms a bloody hemisphere. The tale told here is not without trial and pain, perhaps tragedy; this is no idyll. In a way the blood-red must refer to life, to continuance, and to the commonalities of the brotherhood of man. Yet there is no denying its ominous character.

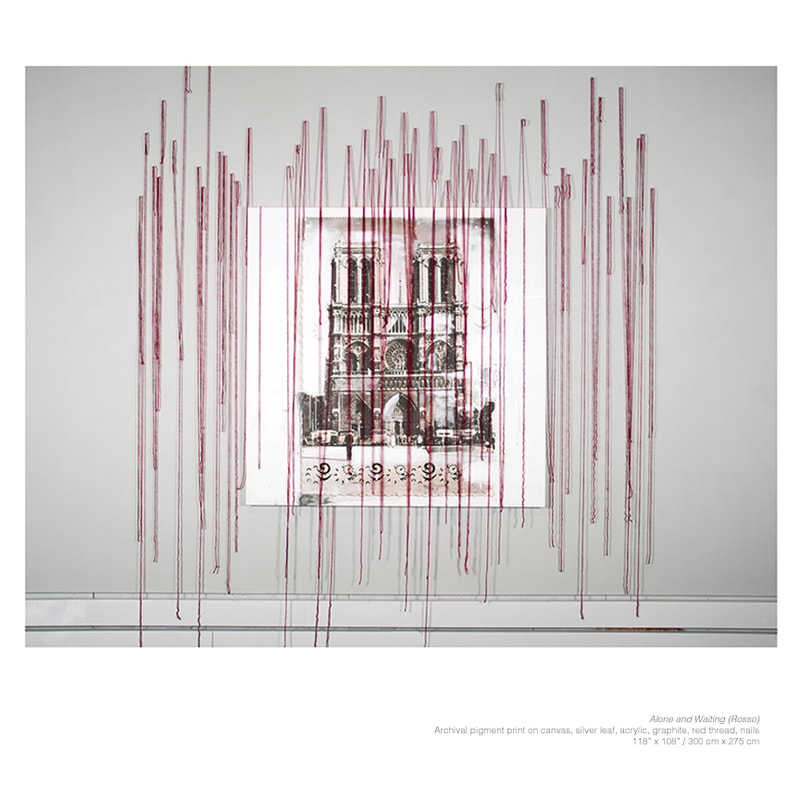

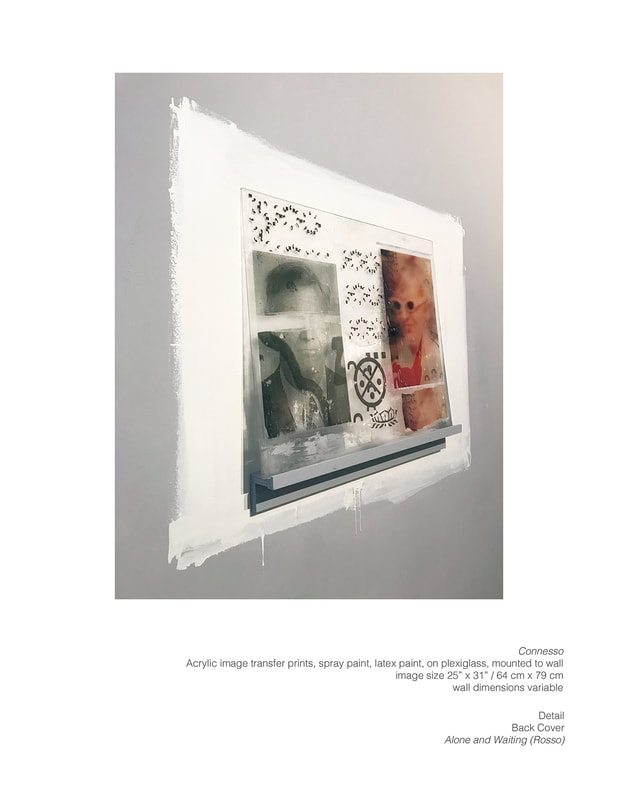

Making this point even more strongly is GV’s “Alone and Waiting,” which is mainly a huge blow-up of what appears to be an antique postcard. This is basically a black and white photograph of the very familiar gothic façade of the cathedral Notre Dame de Paris, shown here sometime in the early 20th century. Between us and the great church stands a man facing away and down, possibly taking another picture. The work’s subtitle is “Rosso” We can imagine there is a story here, probably about lovers and bad timing, or maybe not. In the immediate foreground across the bottom left side of the postcard GV has inscribed one of his ASCII-derived balustrades, a whimsical fence which might also be a line of poetry in ancient Persian, or a cancellation mark from another dimension. And then there is a final, fatal-looking gesture. Hanging as if from an imaginary line well above the picture, all the way down to the floor, and stretching out several feet on either side of the image itself, GV has hung many strands of deep crimson or madder string. This is the visual equivalent of a rumble of thunder. Undeniably it’s a curtain of blood, although it also resembles very long hair, and is both formally effective and oddly uncanny. If the GV’s graffito text is poem-like, this red, red hair through which we see, by which we feel and are akin to the past, is poetry in fact.

By Douglas Max Utter, art critic, artist, writer

Guy-Vincent’s often scroll-like mixed media works re-imagine the long, opaque quality of time’s passage, and the persistence of human identity half-submerged in its tide. Working on canvases or Dibond panels abutted in series, or on very large sheets of thick artists’ paper, GV mixes images and calligraphic marks, half-painted over as if with white-wash, or perhaps (metaphorically) sea-foam. These written traces and forms float in pentimento-riddled layers, hinting of mythic paradigms and distant epochs. Their overlapping suggests the circulation of information and differing perspectives, rolling between contemporary communications technologies and the genetics of genealogy.

In his search for a personal artistic language GV first turned to personal documents and photographs, which traced his own family’s spread across the Atlantic to the New World. Emotionally powerful large-scale blowups of faces and buildings became emblems of vanished worlds in these works, stained and crisscrossed with areas of red and white. Traces of mysterious marks appear and disappear like half-buried ornamental friezes or inscriptions in an ancient alphabet -- like the trove of ancient, daily records recently identified on papyri used as Egyptian mummy wrappings. GV’s half-pictorial marks (which he generates from manipulated typescript) are now characterististic of his works as a whole, along with other expressive gestures, especially pools or stains of white and red paint. They reflect GV’s long-standing interest in graffiti and well-known symbolic languages, like standard text-driven computer programs and the pictorial potential of numbers and letters, serifs and punctuation. Since the 1990’s GV’s work has operated at the boundaries of public and private expression, emphasizing formal qualities of modern communications activities, linking fine art to advertising and propaganda. Always concerned with what could be called the aesthetics of data, both big and small, he now moves more quickly though human cultures, using vehicles available on the internet. GV’s more playful expressions have become widely known on Twitter and Instagram, especially his hypnotic video loops and graphic experiments, which turn patches of ASCII into micro-gardens of interlocking shapes and lines.

In the show “Codes and Identity” new works like “Torre” (“Tower” in Italian) are as much as fifteen feet tall, or lead for yards across the wall horizontally like watchtowers or canals. Throughout the current exhibition they look a lot like documents, but also like the spires and itineraries of great journeys. Encoded in their shapes and dimensions are memories of the scope and reach, the sheer scale of human migration, reminding us of the maps made with feet that have unfolded across the earth and oceans of every family’s past. In their details they sample a dimension of record-keeping and mark-making that has existed alongside every civilization from its rudest beginnings. Sumerian tablets, hieroglyphic inscriptions, petroglyphs and the tally marks and symbolic knots of herding cultures, Babylonian star maps and the invention of mathematics, all can be glimpsed beneath the membrane of our own cultures systems of symbols. The fact that through not only theory but microphotography we know that our own bodies and everything living are in some sense “written” by DNA, inscribed in reality by streaming, chemical sentences which actually look like a kind of writing, is a sort of graphic parallelism that also sets off its echoes throughout GV’s reveries. Gradually a sketchy semiology of the self emerges – phrases composed of paint and ink and imagery, overwritten with traces of written languages in several languages and alphabets around the globe. A large vision of humanity’s deep history and far-reaching webs of communication hang behind the columns and friezes of his symbolic improvisations, and a sense of persistent human personalities, peering from forgotten times and moments infinitely numerous.

“Tempo,” which is four feet by 185 inches, unwinds the hidden trails and traumas of a long trip, long ago. Here as elsewhere one of GV’s tropes is the idea of musical notation, as it measures song and sound, emotion and duration, stepping along the staff. So much information is packed into a few lines, somewhat as worlds of experience and ability, of differentiation infuse every micromillimeter of organic matter. In this work GV uses graphite and spray paint, gesso and latex and coffee, spread, poured, or inscribed on canvas. Near the beginning, along at the top of the first (perhaps) or left-hand section, can be seen the face of a serious, old-fashioned boy, dressed up in a tie and formal jacket, as if for a passport photo or a confirmation celebration. The photo – and the face – recur near the right-hand margin of the piece, much larger this time, as if nearer. In between there are many rectangles that could be windows, or parts of a filmstrip, or train cars. And here and there a bristling little linear ridge, like an indication of a mountain range, appears through the stained manuscript-like surface. It could be a quick sketch in a letter home, o just a doodle. The first panel ends with a column of red, accompanied by a vertical series of marks that might represent a number. At the bottom corner of a middle area a puddle of red forms a bloody hemisphere. The tale told here is not without trial and pain, perhaps tragedy; this is no idyll. In a way the blood-red must refer to life, to continuance, and to the commonalities of the brotherhood of man. Yet there is no denying its ominous character.

Making this point even more strongly is GV’s “Alone and Waiting,” which is mainly a huge blow-up of what appears to be an antique postcard. This is basically a black and white photograph of the very familiar gothic façade of the cathedral Notre Dame de Paris, shown here sometime in the early 20th century. Between us and the great church stands a man facing away and down, possibly taking another picture. The work’s subtitle is “Rosso” We can imagine there is a story here, probably about lovers and bad timing, or maybe not. In the immediate foreground across the bottom left side of the postcard GV has inscribed one of his ASCII-derived balustrades, a whimsical fence which might also be a line of poetry in ancient Persian, or a cancellation mark from another dimension. And then there is a final, fatal-looking gesture. Hanging as if from an imaginary line well above the picture, all the way down to the floor, and stretching out several feet on either side of the image itself, GV has hung many strands of deep crimson or madder string. This is the visual equivalent of a rumble of thunder. Undeniably it’s a curtain of blood, although it also resembles very long hair, and is both formally effective and oddly uncanny. If the GV’s graffito text is poem-like, this red, red hair through which we see, by which we feel and are akin to the past, is poetry in fact.

By Douglas Max Utter, art critic, artist, writer